New from Troika

Bernard Ashley on Writing Historical Fiction

Bernard Ashley’s gift is to turn what seems to be low-key realism into something stronger and more resonant. Philip Pullman

Since the publication of The Trouble with Donovan Croft in 1974, Bernard Ashley has produced a stream of emotionally rich, hard-hitting children’s fiction. Frequently, these brilliant stories dramatize the experiences of children whose lives are touched by momentous political events.

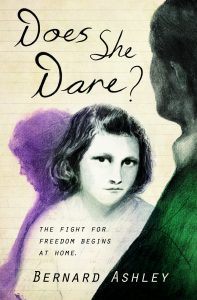

His latest, Does She Dare?, is a gritty, tender novel set against the backdrop of the women’s suffrage movement. In her struggle to defy her violent father, sixteen-year-old Lizzie Parsons shows us just what it takes to stand up to abuses of power, both personal and political.

We spoke to Bernard about his work, and in particular the challenges of writing historical fiction.

As well as being hugely memorable, Lizzie and her mother, Alice Parsons, seem so distinctively of their time. Could you tell us how you developed them, and how you went about ensuring that their thoughts and attitudes reflected the sensibility of the period?

None are based to any big degree on real people. Each grew and developed in the writing as I went along. Lizzie became my most loved, and I cared deeply about what happened to her in every aspect of her life. I feel like a father to her.

As well as having aspects of my grandmother in her, Alice is also like my mother, deeply loved by my dad. Even given WW2 and evacuation – I went to 14 different primary schools – I had a brilliant, loving childhood.

My parents were born in 1905 and 1908 respectively – so for a long time I had a handle on people who lived through the periods I’ve written about. Their attitudes to many things didn’t seem to change very much through their lives, so I do feel that I had a conduit to the early twentieth century, especially through my mother who survived my father by many years. As a boy I lived a few doors away from my maternal grandparents. Nanna Powell would have been 29 in 1912 – could have been my Alice Parsons. I grew up with her and her ways, her sayings, and her attitudes – another conduit. My paternal grandfather had a corner grocery shop in Plumstead. He stands for Mr Smollett – and the story of breaking the stolen eggs is a true one.

While adults understand the difference between history and historical fiction, children and teenagers are arguably less clear. Does this mean you have a different kind of responsibility to them as readers?

Yes. I set out to make things clear. The tone of a conversation will help, and so will a question in the right place. Clarification can also be helped by who’s speaking. When Miss Mitchell describes the death of Charles I we know that it’s history. When Flo hears her account and snaps her pencil we know it’s fiction. I have a strict rule that we’re never in anyone’s head apart from the central character’s. Other characters’ points of view are seen by what they do and what they say – never by what they think. And that mainly goes for me, too. My language is there but my voice isn’t.

I wonder whether you feel a responsibility, too, to your characters, and to the real people they might be perceived, in a general sense, to represent?

I suppose I do, but I haven’t actually thought about it. It seems trite to say, but someone like Lizzie Parsons becomes very real as I get to know her, and I feel the sort of responsibility towards her that I’d have to a daughter.

One of the things I love about Does She Dare is the way the personal and political stories interweave, each amplifying the other. Can you tell us a bit about your starting point for the book? Was it the suffragette movement that first interested you as a subject, or was it the personal story of a girl’s struggle to stand up to her oppressive father?

The starting point was pragmatism. At my age writing a young adult novel set in the 21st century would be difficult, especially since my books are realistic. I no longer have my professional life as a teacher to keep me in touch with iPhones and Facebook and fashion. So my two books prior to Does She Dare? were set in WW1 (Shadow of the Zeppelin) and WW2 (Dead End Kids). I deliberately set Shadow of the Zeppelin to coincide with the centenary of the start of WW1 so I could capitalise on national commemorative plans – helping sales and author school visits.

A couple of years later, on a local history website I came across a photograph of Sutcliffe Road, Plumstead. My mother had lived there at some stage of her life, although she wasn’t in the picture, which was taken on a high day or holiday around 1910. But there, on the pavement and looking somewhat apart, was a striking girl in boots and beret, staring at the camera, daring it – a central character if ever I saw one. She soon became my sixteen-year-old Lizzie Parsons. Now I looked for a centenary date I could work towards – and February 2018 jumped out at me: a hundred years since the first women’s suffrage Act of Parliament. As I researched, the connection between women’s suffrage and feminism broadened the scope of the story.

The book gives us a vivid insight into the courage and resourcefulness of the suffragettes and the great personal price they paid for their actions. Given the significance of the movement, it’s surprising that the experience of these women is not better understood and more often treated in fiction – particularly, perhaps, in fiction for young people. Were you conscious of a lack when you set out to tell this story?

No, I wasn’t – but it’s nice to feel there might be a readership, and since I’m not a High Street name, the school and library market is a good place for me to be.

I had been interested in writing a suffragette story for a long time. A few years ago I got quite a way into the research for a story about Emily Wilding Davison, read her life in various accounts – and now for Does She Dare? I bought several books on various aspects of the WSPU movement. (The EWD idea died when a commission for something else came out of the blue, and I’ve never gone back to it).

Your evocation of London just prior to World War 1 is vividly precise. Could you tell us how you approach research?

I failed History A level – but they gave me a second O level! I’ve never been very academic but I’m driven by interest. When I’ve got a glimmer of a story idea I do the first stage of the research – a sort of feasibility exercise, usually geographical when it’s contemporary. I’ve been to Poland, Romania, Uganda, Ghana, and the Seychelles prior to writing books; and, of course, to all sorts of more local places. I like to see things, smell the air and the earth, with an eye open for some idiosynchratic feature that will make the setting seem believable. Iris, my wife, comes with me on many of my recces, always with her camera. She’ll say things like, ‘Your girl could live there, couldn’t she?’ Iris did this when we went looking for a remote Romney Marsh location for the house in Revenge House – built in my story with timbers from Nelson’s ‘Revenge’. I checked the facts at the National Maritime Museum – and went home delighted to know that the real ‘Revenge’ had been broken up at Sheerness, not so far away. One of those ‘Yes!’ moments.

How do you decide which sources to consult?

I take advice from experts. For each of my war stories I began my research by talking to people at the Imperial War Museum; and for others I’ve been to the Polish Community Centre at Hammersmith, backstage at the Cambridge Theatre, the RAF Museum at Hendon, the Africa Centre at Covent Garden, the newsroom at the BBC, etc., etc. I love this sort of research because I meet interesting people who give good leads.

Hilary Mantel has said that she is ‘happy to make up a man’s inner torments but not the colour of his wallpaper.’ Can you tell us a little bit about how you approach the matter of historical veracity and where the line is for you between fact and fiction?

Oh, I like to know the colour of a man’s wallpaper, and if it’s not on a modern wall I want to know that I’ve got it right. I’m scared stiff of getting things wrong and I check and re-check throughout the different stages of the writing, double-checking again at proof stage. And I still worry.

Iris Dove, whom I acknowledge in the book for her helpful pamphlet on local suffragettes, questioned my using real people in a fictitious setting (like the local Woolwich MP Will Crooks). I’m not afraid to fictionalise a factual person providing they do likely things. In his public speaking I have used Will Crooks’ reported words. Fiction has to fly, not remain grounded.

What do you do about partial evidence and absences in evidence? Do you see these as limitations or opportunities perhaps?

Opportunities. I will invent if it harms no one, although sometimes I cover myself by having a character refer to ‘a rumour about . . .’

Aside from research, does the process of writing historical fiction differ from writing other kinds of fiction? Is there an additional amount of exposition that you have to manage?

A modern child will know their modern version of a bus, so I can take that for granted; but when we’re on a 1912 tram with ‘knifeboard’ seating, if the knifeboard seating is important I’ve got to work in a way of describing it. At other times that sort of detail might not be necessary – someone goes somewhere on a bus (enough said). But I had to dig into my memory and pour over pictures of the Woolwich Free Ferry in 1912 before I could describe the relative positions of Alice and Lizzie in the final chapter.

Does She Dare is an education but there is not a trace of didacticism in it. How did you achieve this?

If I did achieve it, it was through luck – and, I suppose, by my never wanting to be didactic.

Can you tell us a little bit about your origins as a writer?

I’ve been lucky in my writing. My job as a head-teacher in the East End of London in the early 1970s meant that I wrote about what was going on around me. This led to one of the first black immigrant boys featuring as a central character in my first book, The Trouble With Donovan Croft. The book was also one of the first school stories to be set in the state system, which gave it some relevance and connectivity, thanks to the great Mabel George at Oxford University Press. Accessible books. About their own lives. Real. She wrote to me about my submission: ‘Dear Mr Ashley, We are at present considering your novel ‘The Trouble with Donovan Croft”. There is much about it that we like . . .’

Wow! It all started there.

If you would like to read more about Bernard and his wonderful books have a look at his website: www.bashley.com